Metamorphoses, Transformations, Transgressions Postgraduate Symposium: UNSW

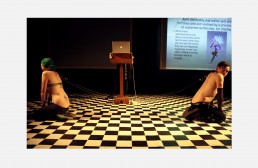

At the Metamorphoses: Transformations, Transgressions Postgraduate Symposium at the University of New South Wales I presented a paper with my early Masters Research on Bodymod and Posthumanism. As this was an experimental arts conference, I was able to include a performative aspect to the presentation, so with the assistance of the team at Polymorph Body Modification Studio, I had two volunteers perform a ‘flesh pull’. As I spoke about how the limitations of our ‘body’ are evolving, the performers physically stretched throughout the course of the talk. A sample of the paper can be found below:

‘Edited bodies – Mapping constructed identities’

Poly Styrene, singer of the British first-wave Punk band X-ray Spex once sung about identity as “the crisis, can’t you see?” while the constructed identities Styrene was discussing were those presented in the media, in relation to the editing process of contemporary bodies the sentiment remains the same. This paper aims to discuss the increasing malleability of our physical bodies and it’s relation to our external representations of such. Specifically the paper will cover a brief history of posthumanism within the realm of cosmetic intervention in the body and their connections with the building of online delineations of self in social media user profiles.

The basis of the research I am undertaking for my MFA is cosmetic intervention in the body, which is essentially bodily modification, however this term aims to encompass more then what is usually classed as body modification. These are process such as but not limited to; piercing, tattooing, sub-dermal implants, sub-dermal anchors, Botox, body augmentation (e.g. breast or buttocks implants), stretching and conch-punching, false nails, hair extensions, hair waxing, eyelash extensions, liposuction, rhinoplasty, skin bleaching and tight-lace corsetry.

The specific personal reasons for these edits are clearly as numerous as they are varied and if there is anything that archaeologists have revealed, it’s that self-adornment is certainly not a new phenomenon. Each addition we make to our body is a strategically placed flag to attract particular potential friends and partners.

“…As we increasingly recognise appearance as ‘statement’ – as we come to appreciate that our choices of appearance style have something to ‘say’ – we begin to see what traditional cultures have known all along: that right at the heart of this symbolic universe which sets our species apart, is the art and the language of the styled, customised human body.”

However, we have always had to rely on external garments and wearables to hide, restrict or accentuate our bodies, it is only in recent years that we have been able to physically edit the actual structure of ourselves to shape our aesthetic. As is so often the case, this luxury has quickly descended into convention. This is particularly evident with the ‘normalising’ of elective body modification, which has led to a global explosion of tattoo and piercing parlours, and a generation that looks out of place as a ‘clean skin’. As William Gibson wrote in the now legendary Neuromancer, “His ugliness was the stuff of legend. In an age of affordable beauty, there was something heraldic about his lack of it”. Similarly this sentiment can be seen in the trend towards modification that is considered ‘beauty enhancement’, spending ones lunch hour getting Botox or at a nail appointment is commonplace for many. The extent of this normalisation has meant that in many cases the term ‘modification’ could easily be replaced with the term ‘grooming’ and establishes our bodies as stages for rhetorical display.

This work was presented at the University of New South Wales in September 2010

Year2010